Back in 2004, in the case D (A Child) [2004] EWHC 727 (Fam), Lord Justice Munby took the unusual, and at the time brave step, of being critical of the court's "impotence" in helping in intractable contact dispute. He said:

"2. From father's perspective the last two years of the litigation have been an exercise in absolute futility. His counsel told me that father felt very let down by the system. I was not surprised. I make no apology for repeating here in public what I then said in private:

"He is entitled to. … I can understand why he expresses that view. He has every right to express that view. In a sense it is shaming to have to say it, but I personally agree with his view. It is very, very disheartening. I am sorry there is nothing more I can do."

2004 headlines (from memory) discussed the courts being impotent in contested cases. Munby accepted (at paragraph 8) that children and fathers suffered due to the bias in the system. Fairness dictates us saying we also see mothers being failed and marginalised when the father is handed sole residence and seeks to alienate the child. Few could argue that in all cases, the children are victims, and in most cases the fathers were, given that the court routinely gave sole residence to the mum, and then failed to enforce contact orders. Many fathers left court crying, and there was no follow up to assess the harm done to the children.

This is why we still maintain the courts should make shared residence orders (or their modern equivalent under child arrangements orders). Power corrupts... and the court handed absolute power to the mother in over 90% of cases. The problem though was never gender, but the issue of control exacerbated by a lack of action by the court when the 'parent with care' ignored its orders. The courts lost trust, and lost control, as parents thwarted orders in the knowledge that nothing would happen as a consequence.

Munby was also pushing for more openness, and wider powers for the court. Some of those powers followed when the Children and Adoption Act 2006 was introduced (coming into force in 2008), but the courts were slow to exercise those powers. Too many cases continued to be left unresolved when, if the resident parent opposed contact, the courts and CAFCASS would wring their hands, looking apologetic, and the child would be left, unprotected, in a toxic environment with their relationships severed by a controlling and at times malicious parent.

We said, time and again, parental alienation should be treated as a form of child abuse.

The Change

There has been a shift in the courts. A new wave of Lords Justice and High Court Judges (Mostyn, Ryder, McFarlane, Parker...) have crept in the door... more capable, more critical, more modern and more open-minded. Munby was ahead of his time (for the courts), but he is not alone, and is now President of the Family Court.

There is now a wide range of case law which might significantly arm the lower courts with tools to combat a form of child abuse where there was little to no protection in past years... in cases involving parental alienation. No assumption should be made that the lower courts are aware of these. It is the job of counsel or the litigant-in-person to make use of them, and be aware of them. The legal profession have their own family law libraries... we endeavour to ensure that unrepresented parties have access to this information too, and that relevant information is easily accessible. All major cases related to parental alienation are now wrapped up in a single library.

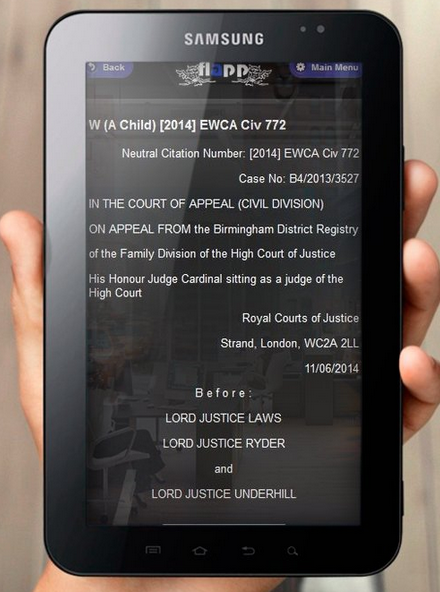

The most recent judgment, given by Lord Justice Ryder (the second youngest high court judge in 250 years, head of judicial modernisation, and now a Lord Justice of Appeal) gives judgment in W (A Child) [2014] EWCA Civ 772.

The W (A Child) [2014] EWCA Civ 772 judgment

There was a finding that the child had been abused by the grandfather, but the mother persisted in

allegations against the father, and prompted the child to make allegations in this regard. The judge had given clear warning of the powers available to him:"[30] At the outset of proceedings I warned both parents of the serious consequences of pursuing this fact finding exercise. Were the allegations now make [sic] of sexual abuse true, then the court would be finding [the child] had been abused twice over, both by the grandfather and, later, by father. It would almost certainly mean, given [the child's] distress, the need for a section 37 report, and probably an interim supervision order, and very careful evaluation of the need to protect, of a risk assessment, and the need to manage, with care, a deeply damaged little girl.

[31] Were the allegations untrue, then mother would be guilty of feeding her with untruthful stories, of an obsessive nature, about sexual abuse. Again, I would almost certainly be directing a section 37 report and making an interim care order, as [the child] would then need speedy removal from an abusive home."

The mother sought to appeal a decision removing her child from her, and placing the child in local authority care via an interim care order. The mother argued that she posed no risk to the child's safety. At appeal, the court agreed with the trial judge, recognising the emotional harm caused by the mother´s having manipulated the child to make false allegations against the father.

The mother sought to appeal a decision removing her child from her, and placing the child in local authority care via an interim care order. The mother argued that she posed no risk to the child's safety. At appeal, the court agreed with the trial judge, recognising the emotional harm caused by the mother´s having manipulated the child to make false allegations against the father.

The judgment had been accepted by the local authority and children´s guardian. The father and they opposed the appeal.

The court accepted it was "unconscionable" to leave the child in the mother's care. Worth noting paragraph 21 of the judgment:

"21. I ask the question rhetorically: given the court's findings, how could the judge leave the child with the mother? No level of sufficient support and necessary protection was described by anyone. To leave the child without protection would have been unconscionable. One has only to consider physical abuse to a child that gives rise to a similar index of harm to understand that such a position was untenable. The submission made on behalf of the mother that her care of the child had in all (other) respects been good or even better than good simply misses the point. More than that level of care was needed to protect this child from her own mother."

Regarding the reasons why the child wasn't placed immediately in the father's care, this is addressed at paragraph 22:

22. The distress that had been engendered in the child, as advised by the children's guardian, sadly made an immediate move to the father impossible.

This, to our mind, is a landmark judgment, with the court, in this instance, placing the emotional harm caused by parental alienation on an equal footing with physical abuse, and accepting that the harm done to the child met the threshold criteria of significant harm.

Caution and Hope

There is no guarantee that such critical examination of cases will be consistent across the country, or even from judge to judge in specific regions. There is no guarantee that the judiciary in the lower courts are aware of what other courts are doing. That said, there is now far more case law to provide litigants and their counsel (if represented) with case law to support arguments and proposals for the court to consider. Whether there will be a just outcome also is also somewhat dependent on their ability to present their case and focus on the strong arguments rather than getting sucked into the minutiae or drawn into tit-for-tat allegations.

What there is now, is some hope for parents and children who face malicious alienation, compared to a decade ago, when there was none.

Click any of the images (except the viagra!) to be directed to content!